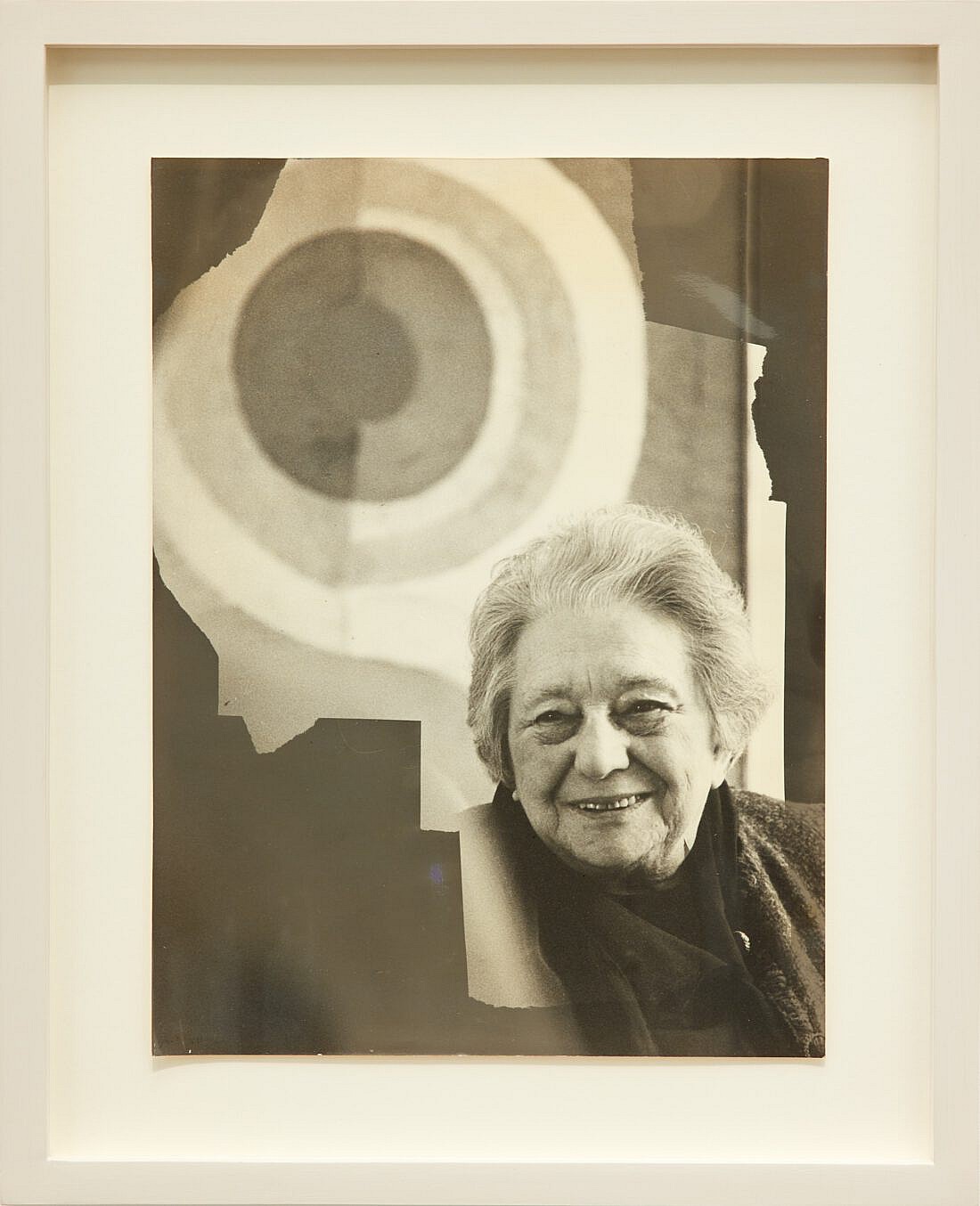

Sonia Delaunay

“One who knows how to appreciate colour relationships, the influence of one colour with another, their contrasts and dissonances, is promised an infinite variety of images.” — Sonia Delaunay

Sonia Delaunay was born Sarah Ilinichna Stern on 14 November 1885 to a Jewish family in Hradyzk, Ukraine, then part of the Russian Empire. While still young, she was sent to live with her maternal uncle, Henri Terk, a successful lawyer in Saint Petersburg. At her mother’s behest, she was formally adopted by the Terks and assumed the name Sonia Terk. Sonia enjoyed a privileged, cultured upbringing, travelling widely throughout Europe. At eighteen she was admitted to the Academy of Fine Arts, Karlsruhe on her schoolteacher’s recommendation. Sonia, however, was more fond of Paris, wishing to settle there, though her parents forbade it. Their permission was eventually granted when she entered into a marriage of convenience with a closeted art dealer, Wilhelm Uhde, in 1908.

Sonia enrolled at the Académie de La Palette in Montparnasse, though she disliked the mode of teaching. She opted instead to visit the city’s galleries and museums, where encounters with post-impressionist works by Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Rousseau would inspire her experiment with causing the colour to interact in such a way that it affects a sense of depth and movement. The young artist also drew inspiration from the condition of her immediate environment — Belle Époque-era Paris — a time characterised by optimism, regional peace, economic prosperity, and cultural innovation.

The Comtesse de Rose and her son, Robert Delaunay, were regular visitors to Uhde’s gallery. Robert and Sonia met in early 1909, and soon became lovers. Sonia was granted an amicable divorce from Uhde and married Robert in November 1910. Their son, Charles, was born in January 1911. The young family were supported by an allowance sent by Sonia’s adoptive family.

The Delaunays’ marriage was defined by their experimentations with colour composition and lyrical abstraction. They became key figures of the Orphism, or Orphic Cubism movement, which is perceived as nurturing the transition from Cubism to Abstraction. Sonia particularly was instrumental in launching an experimental approach to using colour among geometric forms after the largely monochromatic Cubist period.

Inspired by nineteenth-century chemists who theorised that one’s perception of a colour is changed by the colour placed next to it, Delaunay developed a multidisciplinary practice based around works on canvas, paper, and textile — particularly the latter. She collaborated with Dadaist artist Tritan Tzara on a womenswear line, lectured at the Sorbonne on the influence of painting on fashion, and regularly made clothes for private clients and friends. In 1923, she created fifty fabric designs using geometric shapes and bold colours, for a manufacturer from Lyon, and a year later, she opened a fashion studio together with French designer Jacques Heim. In 1925, she opened a fabric shop, Atelier Simultané, and continued to work as a interior theatre designer to support her husband and son. Delaunay saw the eventual decline in business caused by The Great Depression as a “liberation,” according to those close to her. She returned to a painting, designing only for a select few private clients.

Even after her husband’s death in October 1941 and the persecution of Jews in Europe, Sonia continued to grow in prolificacy. In 1964, she became the first living female artist to have a retrospective exhibition at the Louvre. The exhibition comprised 117 works personally selected by Delaunay and was subsequently donated to the museum. She continued to be revered in fashion circles — an entire room was devoted to her fabric designs and dresses at the exhibition L’Expo 1925 at the Musée des Arts Decoratifs in 1965. Two years later, the Musée National d’Art Moderne held a full-scale retrospective of her work. Delaunay had confirmed herself as one of Europe’s most preeminent living artists.

Towards the end of her career, she developed an affinity for working with gouache, experiments with techniques such as hand-knotting carpets, and responded artistically to her early works. She was named an officer of the French Legion of Honor in 1975 and her autobiography, Nous irons jusqu'au soleil (We Will Go Right Up to the Sun), was published three years later.

Delaunay’s last-known interview was published in BOMB Vol. 1 No. 2 (1982). It was conducted in Spring 1978 by David Seidner, to whom she confessed, “I never thought of myself as a woman in any conscious way. I’m an artist. For a long time, I didn’t even know what I was doing. I just had a need to express something.” Delaunay lost her voice shortly thereafter, and died on 5 December the following year, aged ninety-four. She was survived by her son Charles, who became a leading jazz expert and author.