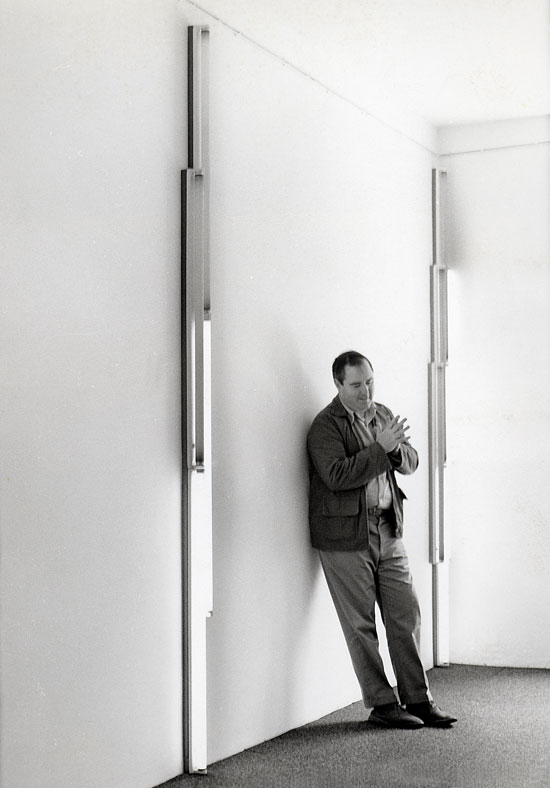

Dan Flavin

Dan Flavin was an influential American artist, pioneer of Minimalism and the use of light as a medium, who produced a singularly consistent and prodigious body of work leaving an important and lasting legacy that changed the course of the 20th century art.

In 1933 Daniel Nicholas Flavin Jr. was born in Queens, New York, to an Irish Catholic family. He was forced to study to become a priest at the preparatory seminar of the Immaculate Conception in Brooklyn. He recalled “Soon religion was forced upon me to nullify whatever expressive childish optimism I may have had left”1. After which he enrolled in the meteorological branch of the US Air Force with his twin brother, David. During his military service Flavin developed an interest in art and pursued this interest with the extension program of the University of Maryland in Korea. Upon his return to New York in 1956, Flavin further followed his passion attending the Hans Hofmann School of Fine Arts and studying art history at the New School for Social Research, before finally completing his studies at Columbia University with a painting and drawing course.

Flavin’s early work reflects his interest in Abstract Expressionism. By 1959, he had begun assembling and creating collages from objects found in the street, most notably crushed tin-cans. At the time, the young artist was working as a mail room clerk in the Guggenheim Museum where he met and befriended fellow artist Sol LeWitt, critic and curator Lucy Lippard, minimalist painter Robert Ryman and art historian Sonja Severdija, whom he married two years later. In 1961, he presented his first solo exhibition of collages and watercolours at the Judson Gallery in New York. That summer, while working at the Natural History Museum, Flavin began sketches of sculptures made of electric light. In the same year, he translated his sketches into assemblages he called “Icons”: eight monochrome paintings with electric bulbs around the edges, one dedicated to his brother David, who had recently passed away. The reference to icons is emblematic of his work. It is a relentless conceptual exploration of space and light. “I like art as thought better than art as work”, “I've always maintained this. It's important to me that I don't get my hands dirty. It's not because I'm instinctively lazy. It's a declaration: art is thought.”

From 1963, Flavin worked solely with fluorescent tubes of industrial manufacture which he assembled differently according to the installations. He only used six lamp colours: red, yellow, blue, green, pink and ultraviolet; and four whites: cool white, warm white, daylight, and soft white. His dedication to simple forms, use of industrial materials and symbolic meaning allied his practice to the work of both Donald Judd and Sol Lewitt. Experimenting with light, colour, and space throughout the 1960s, Flavin began to reject studio production and refused to call his art ‘work’ or ‘sculpture’, preferring instead to refer to each construction as a ‘proposal’ or an ‘installation’. In most cases, Flavin listed his installations as Untitled but added a dedication parenthetically, like his famous Monuments to V. Tatlin, an homage to the Russian painter, sculptor and architect Vladimir Tatlin. In 1970, Flavin began issuing certificates on graph paper, which included diagrams of the work, written descriptions and his signature. His intention was to protect the works and to promote the care of the objects.

In the late 1970’s the artist began a partnership with the Dia Art Foundation that resulted in the making of several permanent site-specific installations and led most recently to the organization of the traveling exhibition, Dan Flavin: A Retrospective (2004–2007). The artist focused on site-specific large-scale installations for diverse locations as Frank Lloyd Wright’s spiral rotunda at the Guggenheim Museum or the converted nineteenth century rail station in Berlin, now the Für Gegenwart Museum. While the scale had increased, the material, aesthetic and reflection that Flavin demonstrated in his earliest light experiments were still evident.

The artist died in Riverhead, Long Island, New York, on the 29th of November 1996. At Flavin’s death many intended works remained unbuilt and uncertified; the Flavin Estate elected not to issue any work not certified during the artist’s lifetime. A few installations were completed posthumously, including the outstanding Chiesa di Santa Maria Annunciata in Milan. He remains one of the most memorable and innovative artists of his era and his installations are considered icons of Minimalism.

1 Dan Flavin, “… in daylight or cool white.” an autobiographical sketch (to Frank Lloyd Wright who once advised Boston’s “city fathers” to try a dozen good funerals as urban renewal) Dan Flavin: The Complete Lights, 1961-1996, 2004, p. 189.

2 Dan Flavin interviewed by Phyllis Tuchman, Dan Flavin: A Retrospective, 2004, p. 194.